A thousand faces of a counterinsurgent

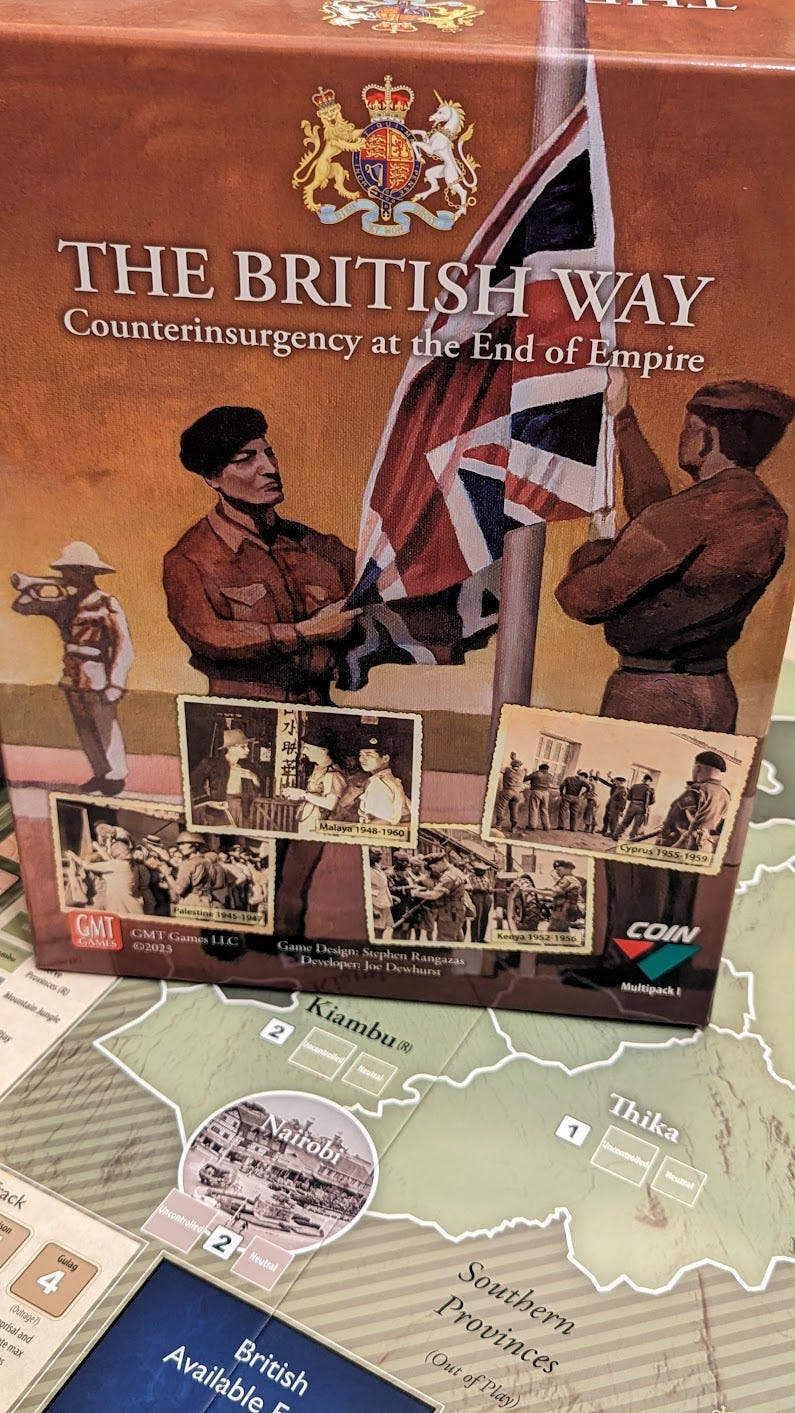

A review and discussion of the educational use of The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire, designed by Stephen Rangazas and released by GMT Games

As the Spring semester is getting closer, it’s about time to review course syllabuses, including for the class on wargaming. This means, I also must decide what games should be used. While changes to plans are always possible based on the interactions with students, having a core structure is helpful in managing the process. One of the games I will use this year is The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire designed by Stephen Rangazas, an entry in the COIN series created by Volko Ruhnke and published by GMT Games. As a disclaimer, I received the game for teaching purposes from GMT. I am very grateful for it, as I couldn’t use the game to the same extent otherwise. However, this fact in no way affects my impressions of the game itself expressed here. The text focuses on The British Way, but also outlines my thoughts on why COIN games are exceptionally fit for classes focused on wargaming as a method.

Classroom as COINroom

COIN series has several strengths, when considering them for classroom use:

Clear relationship structure between the players (COIN vs. insurgents), making it easy to define them as a model and sketch it using broad strokes. This is very useful in helping students to see games as models, sharing similarities with those they had seen in previous social science classes.

Symmetric information, making sure that explanations can be made to all players without affecting the game flow and ensuring that everybody is on the same page. While the difference between perfect and imperfect information is useful to explore, for a start games without hidden information are more helpful. It also means that students from different teams can help each other as well.

Asymmetric players, demonstrating how games can model very different agents and interpret their victory conditions.

Last year I used Cuba Libre to demonstrate this during the class, and it worked. However, there were specific challenges too. The four players with (mostly) unique actions meant a more challenging explanation and game flow. Due to this, discussing it as a model was also not as straightforward due to a higher level of complexity, and understanding the asymmetries and interactions, limited the number of turns we could play during the classroom time.

This is why I was very excited about The British Way. The game comes as a multi-pack of four scenarios (though each is an individual game on its own, I use the word scenario to make the text clearer) for two players, where one player takes the role of the British Empire and the other, one of four insurgent factions. For the use in education, this immediately showed potential benefits:

Two asymmetric factions per scenario means that less time is needed to explain the game. When playing with a friend without wargaming experience, rule explanation and playthrough for one scenario took about an hour and a half. Thus, even two sessions are feasible during one class (we have two 1.5 hour meetings back to back).

Explaining the game as a model is easier than for most of the other COIN, as interactions between two factions must be modelled (of course, accounting for external factors as well). This is very good for introducing the concept of games as models similar to those that students have already encountered in earlier courses.

Having different options to choose from in a multi-pack, means that groups of students can play different scenarios and then discuss their similarities and differences in mechanics and theme.

These were my impressions about the game structure and how it could be used for education. But what about the game itself and what other lessons can it help with?

A story in four acts

The British Way is a story of the End of the Empire, as the title says. While the previews titles in the series all told a story as a single piece, be it something as brief as the Finnish Civil War or the turbulent recent past of Vietnam, The British Way offers a different experience. It takes the final decades of the British Empire and tells four episodes of this larger drama in detail. The episodes are Palestine, Malaya, Cyprus, and Kenya, all well chosen to give different stories leading to the larger idea behind the game that it was not so much a winning over hearts and minds of local populations as reliance of force to maintain control.

Each scenario depicts a different type of struggle, even if similarities are necessary there, the key being Political Will. As an insurgent, reduce it enough and you win, the Empire will not be willing to remain. As the British, keep it high enough, and the domestic audience will want to keep control of the land and the people. By moving the look from the broadest picture (or rather leaving it to the campaign) and zooming-in to the specific parts of the End of Empire, designer Stephen Rangazas also makes the story more personal. Following the events coming through the cards and reading up on them in the rulebooks. Having had little knowledge of most of the stories told in the game, it proved to be very enlightening both through the models of the scenarios and through this accompanying information.

What the four acts of The British Way story achieves is demonstrating how by restructuring the game and cutting some of the complexities, a COIN series game can tell broader stories. In this case, covering different decades and different continents. Even then the games tend to take a macro-lens. This may well be illustrated by the designer’s choice to give agency to Irgun in the Palestine scenario. The largest faction opposing the British, Haganah, functions as an external factor of the game system instead of being controlled by the player. While both players have interactions with it (another good task for students when describing the model), the story told is mainly about the Irgun, its tactics, and the British response. Haganah is there, it is important, but the story of the game is sharper.

The risk here, of course, is with making sure that all four games in the multi-pack use a similar framework, but each remains specific enough to tell an exact episode of the broader story. The game succeeds in this. Fittingly, one side played is always the British Empire, but its opponent differs. Now, it is Irgun and Lehi in Palestine. Now, it is the Malayan Communist Party in Malaya. Now, it is the EOKA (National Organization of Cypriot Fighters) in Cyprus. Now, it is the Mau Mau in Kenya. Each of these organisations aimed toward a similar goal, expressed by the Political Will in the game, but each faced different constraints and different contexts, leading to variation in tactics. Consequently, each situation involved different responses from the British state. Thus, even playing that side each scenario provides a unique experience.

Mechanics of insurgencies

Mechanically, the game uses the core of the COIN system with added variations to make it work for two players. Each turn a new card is drawn, players act depending on their position of the initiative track. This position may allow them to play a limited operation, an event, or carry out an operation plus a special activity. Although the cards do not include the faction sequence, the dilemma for players is still strong. The games are shorter, and timing of operations can make or break the Political Will during Propaganda cards. The flow is simpler, but decisions can be just as excruciating. At the same time, as a player you feel a bit more in control of your destiny than in some of the more complex games in the series, where waiting for your turn can mean a significantly changed situation once you get to make a move again.

The other concepts are also there – underground and active cells, towns and other spaces with varying terrain, support, and control. However, the game is far from ‘same old’. First, each scenario uses only those standard COIN elements that are needed. Irgun couldn’t be expected to take control, while the Mau Mau could. This helps to crystalize the core mechanics that are needed to model a particular situation and tell that particular story. Each scenario also brings its own specifics to reflect the different responses to the insurgency, whether through establishing New Villages in Malaya or the use of Curfews in Cyprus.

I think this variation in the adoption and dropping of what’s usual and mixing in what’s new and specific, helps The British Way build a strong narrative. It makes your decisions more thematic and often uncomfortable. Four scenarios and the campaign give enough room to explore it. Meanwhile, the elements carried through all the scenarios, such as the Political Will, provide a backbone and a unifying line to the overall game and the campaign. After all, despite different means and different contexts, it was a lot about the willingness to keep the parts of the empire.

The British Way brings a lot of new to the COIN series. The multi-pack structure allows extending the scope of stories that the games can tell. By providing a more focused experience they also enable a clearer agency to the factions modelled. I do not mean that the other COIN games do not have it, but here it comes through especially strongly. Everything that is done in a game affect both factions of the scenario.

Stephen Rangazas is currently working another COIN multi-pack, The Guerilla Generation, about the Latin American insurgencies during the Cold War. I am definitely looking forward to what it will bring to the series and the stories that it will tell.

Other lessons for the class

At the start of this piece, I listed why COIN series in general and The British Way in particular are mechanically good for classroom use. The approach I am planning to use in the Spring semester course is to have four groups of students play two of the scenarios (trying to select the most differing ones). They will then be asked to map the agents of the model and their interactions, how the different actions lead to achieving one goal or another.

However, modelling is not the only lesson to be learnt and discussed. Here, in Vilnius, our experience with the British (not yet empire) is quite limited, except for future Henry IV joining a crusade against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Thus, the narrative of the game is very likely to be new and (nearly) unheard. This can help to broaden the discussion from how the game models the processes to why there were differences in insurgent and counterinsurgent tactics. How Political Will is affected in each case and what its meaning is. My hope that these two lines of discussion – modelling and the history behind the game – will help demonstrate how game mechanics can link with actual history and games can become more than just a fun activity. I hope very much, that the uncomfortableness of actions and events will also naturally emerge in the discussion. If not, I’ll help to bring it to the spotlight. It is one of the key parts of the story of the game and one of the key lessons it provides.

The British Way will likely not be the first game we’ll play in class this coming Spring, but it will be one of the first ones. No hidden information, clear focus, reduced complexity, and playtime (compared to other COINs) means that when we come to discuss games as models, it will be an example fit for the classroom environment. And I hope that the lessons learnt will be broader than it. The game provides enough material for this.