All the pretty little games

How light games can help to achieve learning objectives in the classroom.

Talking about wargames, including those that are educational or professional, often creates an impression of complexity, and often rightfully so. Yet, smaller and lighter games can provide some very useful lessons too. First and foremost, it is important that games used in education are aligned with specific learning objectives. Otherwise, why use them in the curriculum? That could be an interesting extra-curricular activity, but it would remain outside of the core educational path of the students. It may seem that large and complex games are best adapted for learning purposes, but when it comes to teaching about mechanics and reading games as models, smaller games might just do an excellent job, if chosen appropriately. Here, I would like to express my thoughts on how light games can find their place in education.

Introducing mechanics

One thing that lighter games can help with is introduction of specific mechanics. For students who have limited exposure to board games in general or wargames in particular, getting a first hand experience with common mechanics and their function as thematic metaphors helps when designing their own game prototypes. And, as the semester length does not allow exploring a large number of games, the ones that are played will likely have a very significant influence. For example, in earlier years, inspiration from Maria (Richard Sivél, Histogame) and The British Way (Stephen Rangazas, GMT Games) was very clearly seen in some of the students’ prototypes. Of course, these are not small games as such, but just to illustrate why exposure to common mechanics is important. I will highlight two light game examples here.

The first one, Watergate (Matthias Cramer, Capstone Games), works great for introducing card-driven mechanics. Here, one player takes the role of Nixon’s administration, while the other plays as The Washington Post journalists trying to reveal the illicit activities against political opponents. Both players have their own set of cards, and have to choose between the event and points for actions, when playing them. The game is rules-light, there are not many complexities involved, and within a duration of a seminar more than one session can be played. As the key mechanics are card-driven decisions and tile placement on a bulletin board, connecting (or disrupting) the evidence connections. An advantage is that the topic is generally well known, so it is not difficult to grasp what is happening, and how mechanics reflect the theme. And them, after Watergate it is less challenging to take a step toward more complex CDGs.

Another game (which is new for me, so I haven’t had a chance to try it in class yet) is Port Arthur (Yasushi Nakaguro, Nuts! Publishing). Here, the players take the roles of the Japanese and Russian navies to fight the war of 1905. This game can be very helpful in highlighting the role of luck and risk management in games. The rounds have variable duration, as players roll dice to see who gets to act first or if that’s the end. Then, naval battles and movement of squadrons also involve making decisions on rolls to be might, actively asking the player to choose between higher risk - higher reward and lower risk - lower reward.

Reading a game as a model and giving it a narrative

Our course at ISM focuses specifically on looking at games as models. This semester, students come from the political economy, economics, and finance programmes, and by the time we have the wargaming class, they have already had several classes that discuss models and modelling in social sciences. Whether on game theory, on econometric and causal inference models, or still other approaches, the core understanding of the role and importance of models has been built before. Starting from this background, we now explore how games can serve as an additional tool in modelling social reality.

Certainly, wargames differ from other social science models (or why else would we need them as a modelling method). Instead of fully assuming what decisions would be made, they require participants to make the decisions. Instead of just calculating relationships based on regression models, they suggest relationships between factors, but leave space for uncertainties and players’ exploration. I talked about this a bit more at a Georgetown University Wargaming Society (GUWS) webinar last year.

Coming back to the topic, in order to learn to read wargames as models, lower complexity and smaller scale games might help well. I would like to stress three examples here, though certainly way more could be discussed. Yet, it is no less important, that players are also immersed, so even smaller games need to form a narrative around the model.

Last Fall, I received an invitation from the youth branch of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union, to present wargaming to teenagers. Naturally, it should also include some interactive activity and last about 60-90 minutes in total. That is, including the presentation part. Given these time constraints, the game should be both representative and simple. Also, as the number of participants is in the dozens, running the session with physical games would be difficult, so somehow, I should run a game on the screen with players making decisions jointly. Here, Take That Hill! (Phil Sabin, version used released by Fight Club International) worked well. It has scenarios of varying complexity, and starting with the most basic one it gives players 3-5 choices of action per unit, which I could easily fit in a Slido poll. So, the game was shown on PowerPoint slides, and participants used their phones to vote in a poll on what should be done each turn with each unit.

Take That Hill! is a tactical game, where a platoon needs to take a hill, with enemy located at the top. Action choices are quite straightforward - move, stay, shoot to suppress the enemy, rally. It is fairly straightforward and helpful to introduce specific concepts of wargames (e.g., hexes) and test some tactical understanding. It is easy to internalize after taking a turn or two. Moreover, the game also comes with a visual representation of the model behind the game, and so it serves as a good point of discussion on how a wargame is a model, and what are its advantages. Generally, the reaction I get after demoing the game and showing the vizualization of the model, is that it looks much more complex and difficult to read than the game itself. This is one of the uses of wargames (including light ones) - making it easier to internalize the model. Even if the rules may not be that easy to grasp initially.

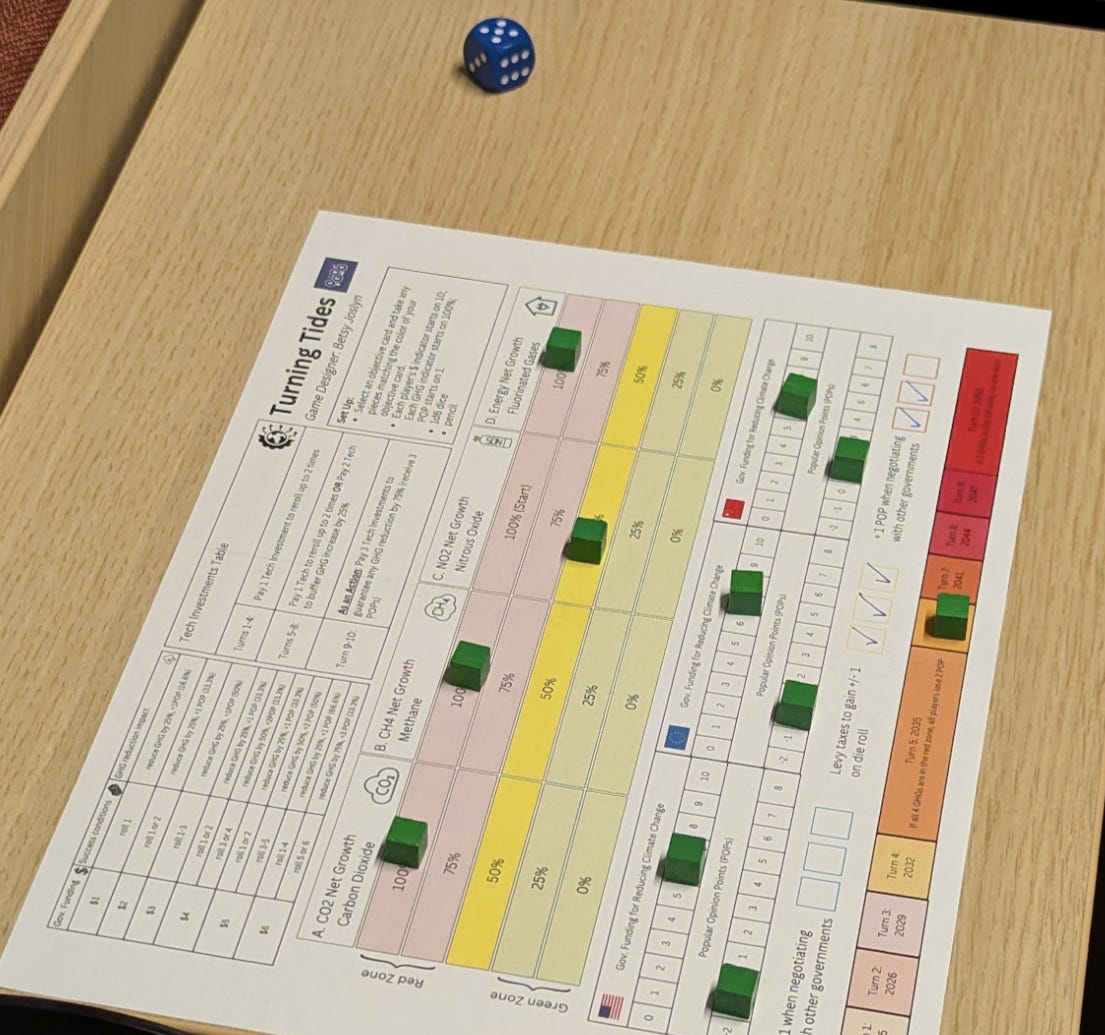

Another good example is a print and play game Turning Tides (Betsy Joslyn, GUWS) that I use quite often in workshops or in my game theory classes (again, to illustrate variation in modelling approaches). It is a three player game about addressing climate change that contrasts common interest in reducing greenhouse gasses and individual interests of world’s major economies (the US, the EU, and China). Here, through limited actions, the underlying model of pursuit of interests becomes clear - what exactly is modeled and what the interactions are. When playing this game by the end of my master’s course in game theory, students can connect the game theoretic concepts we learned to what is happening in the game. Yet, the game format also reveals additional processes that are not (easily) captured in game theory models.

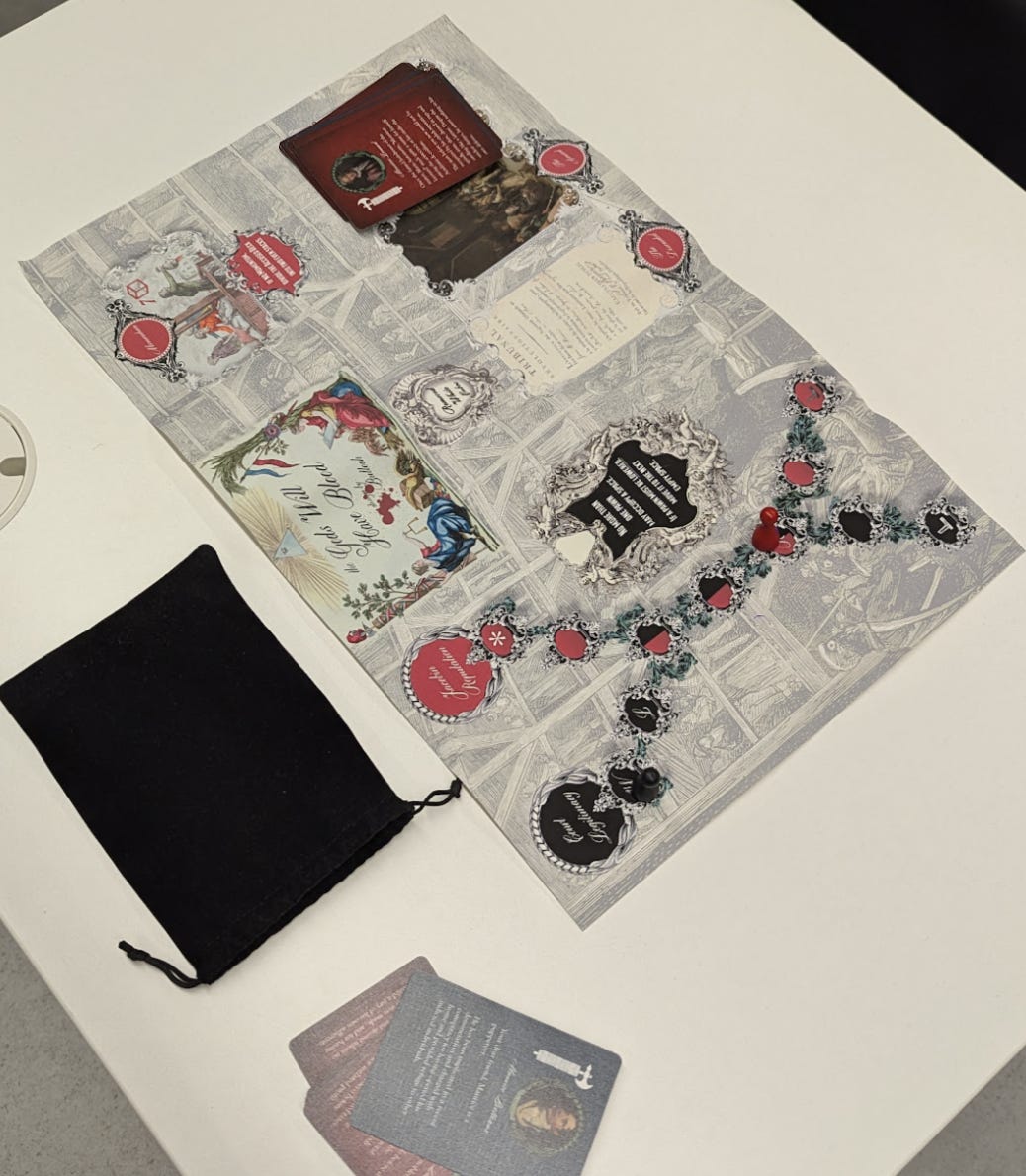

Yet, a game should also tell a good story for greater immersion (listen to a related and very interesting discussion by Ian Curtiss and David Banks). Here, I would like to refer to The Gods Will Have Blood (Dan Bullock, Lock Horns Games), a solitaire game about a magistrate during the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution. The model is relatively uncomplicated, but the way the game builds the narrative, is excellent. Each round, the player (or players - I asked my students to vote on the guilty/innocent decisions and make a joint decision in a rather pompous and ceremonial way involving red and white cubes and a red and white cup) gets a piece of background information about the person being judged. Whether they are found guilty or innocent, there will be some mechanical effects to resolve, but they will be presented first through the story.

Finally, if moving to game series, it is worth looking into the least complex entries. Here, The British Way, one of the entries in the COIN series can serve as a great example. Although definitely quite a bit more complex than the other games mentioned here, it is a set of four scenarios smaller than what you usually find in the COIN series. This is an advantage in both introducing the system and this approach modelling counterinsurgency. For this, I ask students to pre-read about the Cyprus and Malaya insurgencies, and then we spend both the lecture and the seminar time (around three hours in total) with the game. It helps to learn to approach models with strong asymmetry, while still keeping just two agents (the British and the insurgents). Then, more complex games in the series can be introduced. One additional resource that helps here is Volko Ruhnke’s GUWS presentation on designing COINs.

From small to micro

Turning Tides is also a microgame, another topic worth discussing here. Connections UK last year included a great workshop on them run by Evan D’Alessandro, Josh Kovan, and Thomas Danger. You can find the slides of the presentation here and listen to the audio here. The key takeaways for me here are that microgames:

Have immediate utility

Focus on 1-2 ideas

Are accessible to different audiences

This makes them very well suited for a classroom. First, students don’t need to have (or acquire) highly specialised knowledge about the topic. Second, due to focusing only on a very low number of elements, the models and their mechanical representations are relatively simple to see through the model thinking perspective. Third, you can focus on how well mechanics works as metaphors for the topics they are supposed to represent. Again, as there is a smaller number of elements depicted and fewer mechanics used, which makes it easier to start with.

Microgames have a great advantage of often being easy to get hold of and copy, as numerous come in a print and play format. From GUWS microgames (including Turning Tides) to Indo-Pacific and Europe focused ones organized by Sebastian Bae. Finally, you can always run a short game jam with participants developing their own microgames. Working within the expected scope and complexity restrictions can help a lot with design skills.

To summarize, lighter games are useful. Whether in learning to read games as models, getting acquainted with new mechanics, or exploring design constraints, they might serve well. They can also be a stepping stone moving towards more complex games, which then may lead to meeting more advanced learning objectives.

It would be helpful to see some images of the games discussed.